|

|---|

Monday, September 27, 2010

Yeah, she works for a living. But is she really responsible for the Holocaust?

I found this photo by googling "Polish cleaning woman." This photo appears here.

Susan Isaacs' bestselling novel about WWII, "Shining Through," describes a "Bohunk, Slavic" home care attendant who is more chimp than human.

Best-selling novelist Susan Isaacs. Source.

Isaacs' first bestseller

Bieganski is everywhere.Often, when I mentioned that I was writing my dissertation on stereotypes of Poles and other Eastern European, Christian, peasant-descent populations, i.e., "Bohunks," protesters would insist: "Poles? Who stereotypes Poles? No one stereotypes Poles!"

In fact, though, Bieganski – the brute Polak stereotype – is everywhere.

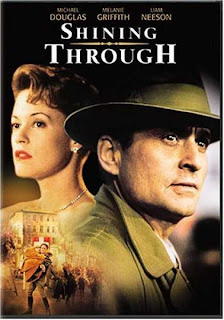

I recently read Susan Isaacs' "Shining Through," a NYT bestseller and subsequent film. According to Wikipedia, all of Isaacs' novels have been NYT bestsellers; she's written for films, the NYT, politicians; she is a member of PEN and several other prestigious groups.

"Shining Through" is trash, but very, very popular trash, and it features a Bieganski-character, as described in my Amazon review, below.

The Bieganski character in "Shining Through" appears only briefly and is not essential to the plot. This character could have been deleted with no damage to the book.

That this character is so expendable makes its inclusion all the more instructive. Isaacs' worked to include an unnecessary "Bohunk" character who "smells like a toilet" and looks more like a chimpanzee than a human being.

All right, so what? Who cares if American authors, political speech writers, script writers, and community leaders like Susan Isaacs hate Poles?

Here's the so what, that anyone, not just a Pole or a Jew, might care about. The Bieganski character exists at least partly to distort Holocaust history. For more details on that, please see chapter seven of my book, "Bieganski."

Below please find my Amazon review of "Shining Through;" this review details the Bieganski character in that very, very popular novel.

Inept Trash Offers Fascinating Glimpse at Ethnic Stereotypes

It's become such a cliché that a fine should be levied every time a reader exclaims, "I don't understand how drek like this gets published!" On the other hand, "Shining Through" is the worst novel I've read cover-to-cover.

I had two reasons for reading it. I suffer from bulky-paperback-novel envy. I have to read for my job, and I'm dyslexic, to boot. When I see readers on a beach, their noses immersed in bulky paperbacks, no seagulls or sand grains distracting them from rapidly turning page after page, I imagine their escape into lushly populated other worlds, memorable characters, and crafty plot twists, as I painstakingly trudge my way through yet another, dreary, work-related text.

The all-caps, New York Times review quoted on the cover of "Shining Through" sold me: "as close to a 1940s movie as a book can get." The Chicago Sun Times promised an irresistible heroine.

By page two I was wondering how much Isaacs paid those reviewers. I kept reading, though; "Shining Through" became a work-related text: an inadvertently fascinating display of American pop culture ethnic stereotyping.

Linda Voss is a secretary in 1940s Manhattan. She works for an exquisitely handsome, blond lawyer, John Berringer. Linda's late, and very good, father was German and Jewish. Her mother is a good-looking, empty-headed, promiscuous, drunken, shiksa blonde.

One night, drunk and lonely, Berringer brings Linda home. She gets pregnant. Making it clear that he does not love her, Berringer marries Linda. They are miserable. For seventy-five percent of the book, Linda is a passive, annoyingly sarcastic, always-the-victim bore who repeatedly sabotages her own life by her lack of self-respect. Linda's constant hectoring of her husband: "You never loved me!" Depicts her as a pathetic harpy, hardly the irresistible heroine promised by the Chicago Sun Times.

Linda decides to become a spy in Nazi Germany. The book is three quarters done by that point. Two whole new casts of characters are introduced, one at spy training school, one mostly noble German resistance workers. There is a happy ending.

In the opening pages of the book, Isaacs establishes that Linda's bosses are rich and powerful by repeating, "They were rich and powerful. They were really rich and powerful." That's not how a clever, or even a merely workmanlike, author establishes wealth and power. You show, you don't tell. You depict a character moving the world in a way that the reader can only dream of – the reader is moved by the character's power. Isaacs establishes that Berringer is good looking by writing, "He was beautiful. Very beautiful. So beautiful." This wouldn't get an applicant into a creative writing program at a community college. The sex scenes are hopelessly dry. About halfway through the book, Isaacs, for no apparent reason, stops using quotation marks, and then starts using them again. Choppy, unclear sentence fragments, aborted descriptions, and asymmetry abound. No feel for 1940s Manhattan is created. The best scenes in the book are brief; they involve Linda, suddenly embracing her Jewish identity that had seemed unimportant to her before, in a face-off with a female Nazi. Those scenes crackle; you wonder why nothing else in the book is as well written or feels as real.

Indeed, I kept reading this inept bore because its encapsulation of gutter-level stereotypes fascinated me. Linda appears entirely biologically divorced from her gentile mother, the good looking, blonde, man-killing, sloppy, drunken, silly, brainless, tramp. How did intelligent, resourceful, multilingual, courageous, competent Linda ever spring from those loins? Linda is very proud of her German-Jewish ancestry. Thanks to that, the book emphasizes right up to its final pages, Linda is orderly, resourceful, intelligent, and a good cook.

Linda's yearning for her WASP, blond boss, John Berringer, is presented a bit like Barbra Streisand's yearning for Robert Redford in "The Way We Were." He is all she can never be: a blond WASP. (Yes, the book uses the word "blond" as frequently as does this review. You can't miss it. Without blondness and all it implies, this book could not exist.) "Shining Through" is much crueler than "The Way We Were." John Berringer, the exquisite blond (there's that word again) beautiful WASP American male, is in fact an empty shell. Linda realizes this, and moves on to an ugly, dark haired man who actually has some substance. Interesting.

Nazi Germany features more noble resistance agents than actual Nazis. Isaacs makes clear that the Germans are terrorized by Gestapo who would torture them beyond endurance if they dared to resist. Isaacs also makes clear, in one of the very few genuinely poignant scenes in the book, that Germans suffered tragically under Allied bombing. In short, Germans are, heck overall, pretty good eggs, the sort you'd like to have for dinner.

Who is the one character in this ethnic minstrel show reserved for real contempt? A "Bohunk" with "one of those Slavic names no one wants to bother to pronounce, Mrshklva or something … she wasn't much of a girl … she looked like a monkey … smells like a toilet … stinky … a stinkpot Bohunk … like a chimpanzee." This is a very minor character; her expendable status makes her indelible and ugly stereotyping all the more remarkable. In a book about WWII, where most Germans, even the really bad Nazis, are clean, good looking, orderly, and clever, the one character who comes in for the most extreme, and offhand, hate speech is a "Bohunk."

0 Comments:

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)